Module 3: Use of the dominant abnormal leaf (ale) mutant to explore inheritance and genetic patterning mechanisms.

The abnormal leaf (ale) FPsc mutant allele is a well-behaved dominant allele that, in both heterozygous and homozygous configurations, causes obvious leaf patterning defects. True leaves of ale segregants are tightly curled (Figure 4a) and ectopic leaf-like fringes of tissue frequently form along stem segments that separate leaves (Figure 4b). Interestingly, the developmental abnormalities that result from inheritance of ale alleles are confined largely to the vegetative phase of the plant growth cycle: young ale seedlings are essentially indistinguishable from wt FPsc and, after advancing through the vegetative (leaf-forming) to the reproductive stage of plant development, the flowers and seed pods that emerge from inflorescence meristems are only subtly different from that observed in wt segregants (Figure 4c).

Figure 4: The dominant FPsc abnormal leaf (ale) mutant. (a) Although seedlings are normal (notice the flat cotyledons), emerging leaves of ale segregants are tightly curled. (b) Ectopic fringes of leaf-like tissues (arrow) form on internode stem segments of ale plants. (c) Effects of the ale allele are largely confined to vegetative phase, inflorescence structures are largely normal and plants are fully fertile.

For the purpose of student education in fundamental genetic principles, use of the ale mutant allele offers the opportunity to disabuse students of the common misperception that wt alleles are inevitably dominant to mutant alternatives, as if the wt alleles are somehow idealized forms that are superior in all cases to alternative “mutant” versions. Among other important insights students might gain by working with the ale mutant allele is that the phenotype of recessive mutant alleles is typically due to a loss of gene function, whereas dominant alleles confer effects on phenotype that may result from gain of functions not ordinarily possessed by loci carried by the reference wt strain.

The educational potential of using the ale mutant is enhanced when students are helped to determine the molecular basis of its phenotype. We are designing exercises using ale in which Mendelian genetic analysis transitions logically to molecular, DNA sequence-based investigations. Helping students to make a concrete connection between overt phenotype and the underlying genotype remains a major challenge in genetics education. Students are too seldom asked to go beyond Punnett square representations in modeling principles of inheritance and so are denied the opportunity to develop a clear mental picture of the molecular mechanisms by which variant alleles and alternative genotypic configurations affect the expression of trait phenotypes. A gently guided exploration of modern genetic mapping experiments and DNA sequence analysis will enable students to unravel the molecular basis of the ale phenotype and to gain powerful insights into fundamental principles that govern developmental biology. Our own experience in coming to understand ale at UW-Madison is a remarkable tale of hard work and serendipity that culminated in an exhilarating “aha” moment of discovery that epitomizes the intellectual rewards of rigorous scientific inquiry.

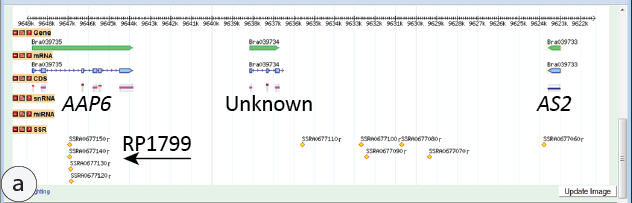

Our experience has also been a powerful proof-of-principle experiment whose results indicate that our students, even those at the high school level, are fully capable of harnessing the power of modern molecular biology to probe and to understand processes that operate at subcellular genetic scales and to make good use of peer-reviewed scientific literature. Thus, during the summer of 2011, several students at UW-Madison, including high school summer interns Andy Rodgers and Kirby Tobin, with guidance from post-undergraduate research interns Jan Lim and Brian Stoveken (pictured in the photo at right with other members of the summer, 2011, team of “rapa artists”), used the molecular markers shown in Figure 3a to map and ultimately to identify the B. rapa locus encoding the ale gene product. By using an open-source web site (http://brassicadb.org/brad/) the students were able to examine the B. rapa genomic neighborhood surrounding polymorphic marker RP1799 on chromosome II, for which no recombinant chromosomes could be detected in the F2 mapping population. Their inspection (Figure 5a) revealed that marker RP1799 detects a (sequence-length) polymorphic locus just ~25 kbp from the B. rapa orthologue of Arabidopsis Asymmetric leaves2 (AS2), a locus known to play a critical role in determination and allocation of cell types within developing leaf primordia between abaxial (lower) and adaxial (upper) developmental fates (Wu et al., 2008). In a very user-friendly and yet comprehensive paper published in the peer-reviewed and prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS), Wu et al. described a dominant allele of Arabidopsis AS2 whose phenotypic effects are essentially the same (although generally less severe) as those of FPsc ale mutants—curled leaves and ectopic leaf-like tissues.

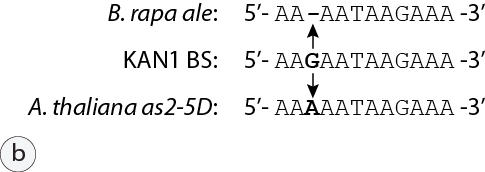

The paper by Wu et al. showed that the dominant AS2 phenotype of the Arabidopsis mutant allele results from a DNA sequence difference (vs. the wt allele) that disrupts a cis regulatory element upstream of the AS2 coding region which is ordinarily bound by the KANADI family of transcriptional repressor proteins. The antagonistic functional relationship between AS2 and KANADI gene products in determining the outcome of developmental pathways is a wonderful example of a paradigm that is now well established in the field of evolutionary developmental biology (“evo-devo”) that describes the pivotal role played “master” transcriptional regulatory proteins whose activities govern the expression of subsidiary subsets of genes in descendent cell lineages to produce tissues and differentiated cell types that are specialized to perform dedicated functions. In the case of plant leaf development, those include activities such as photosynthesis, gas exchange (stomates), and vascular transport of nutrients and chemical energy throughout the plant, and similar principles operate to program differentiation of specialized cell types in other organs of B. rapa, and other plant and animal species. Here’s the kicker: sequence analysis of the ale mutant allele revealed a single base pair deletion at the very same position in the promoter of the B. rapa AS2 orthologue (Figure 5b).

Figure 5: Genomic sequence analysis of ale. (a) Molecular marker RP1799 targets simple sequence repeats (arrow) clustered at a position on the upper arm of B. rapa chromosome 2 and situated within a gene homologous to Arabidopsis AAP6 (Amino Acid Permease 6). 25 kbp away and just beyond a gene of unknown function is the B. rapa orthologue of Arabidopsis AS2. Image captured from a genome browser used to view the genome sequence of B. rapa var. “Chiifu” (http://brassicadb.org/brad/). (b) Sequence of the binding site (BS) for the KANADI1 transcriptional repressor located ~1.5 kb 5’ to Arabidopsis AS2 as described by Wu et al., 2008; the element is identical in sequence and relative position in B. rapa var. FPsc. Arrows indicate the site of nucleotide changes that have been identified in dominant mutant alleles in Arabidopsis (as2-5D) and in the FPsc ale mutant.

In the classroom exercise we are designing to exploit the educational potential of the FPsc ale mutant, students will properly employ PCR and gel electrophoresis as tools that are used in modern genomic research to answer fundamental questions in the biological sciences: what are the mechanisms that ordinarily operate to specify cell fate and organ patterning and how can mutations disrupt those processes, thereby informing investigators of those mechanisms? In the course of mapping using molecular markers students will come to better understand principles of genetic linkage and to see, directly, that meiotic recombination events result in wholesale exchanges of chromosomal segments derived from parental genomes. Students will ultimately use the tools of bioinformatics—genome browsers, BLAST searches, and DNA or cDNA sequence alignments—that reveal evidence of common descent and genomic alterations that may accompany or, indeed, may be mechanisms of speciation. Beyond the experimental manipulations necessary to extract genomic DNA from F2 segregants, to conduct PCRs, and gel electrophoresis, all of the tools needed by students to complete the exercise are but a few (and free!) mouse clicks away.

Click here to see the molecular marker set we've developed for FPsc.