Module 2: An experiment in artificial selection that makes clear the necessity of standing genetic variation to enable a heritable response to selective pressure

This module permits students to apply artificial selection to evoke phenotypic changes in populations over time. Such experiments have been a staple of the genetics/evolution laboratory curriculum for some time, targeting, say, sternopleural bristle number in Drosophila (Gibson and Thoday, 1963) and even trichome density on leaf margins of the WFP variety of B. rapa (Fall et al., 1995). However, a misconception that can be fostered by the use of a single targeted population is that organisms subjected to selective pressures “mutate their way out of trouble,” when, in the short term, adaptation most frequently involves changes in existing allele frequencies. Understanding this point will help students to understand and to share the concerns of scientists to preserve sufficient genetic variability in endangered species to facilitate adaptation to an ever- changing environment.

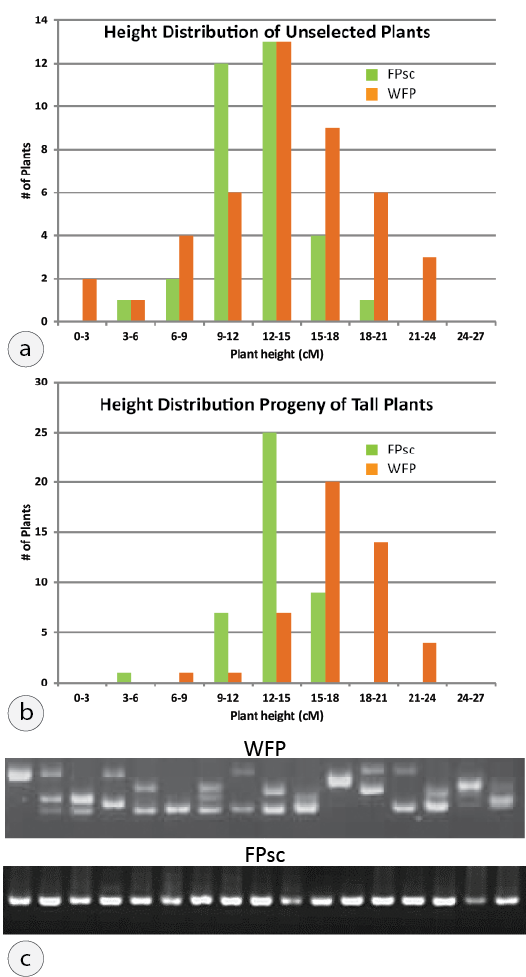

Figure 2: An experiment in artificial selection. (a) Frequency histogram showing height distribution of unselected WFP (orange bars) and FPsc plants (green bars). (b) Results of selection observed in the progeny generation. (c) B. rapa molecular marker can demonstrate allelic diversity within the WFP population that is absent among FPsc plants. The figure shows PCR products of reactions using marker RP825 to characterize molecular alleles carried by 16 WFP (top) and 16 FPsc (bottom) plants.

Our approach to address this common misconception has been to develop an exercise in which selection for a genetically-determined and phenotypically variable trait is imposed by students on parallel populations of WFP and FPsc plants (Figure 2). To date we have validated the expected outcomes of the experiment using plant height at flowering as the targeted phenotypic trait—specifically, selecting for “tall” parental plants—but there is no reason to think that other targeted traits whose phenotypic measure and variability is determined by the allelic variation existing in the WFP cohort would fail to respond to selective pressure. That is, the WFP population has genetic variability and artificial selection can result in successful “breeding” for taller plants; the FPsc line, which is highly inbred, lacks genetic variability and so selection imposed by student breeders will not result in a significant change in average height among the progeny that result from intercrosses among plants in selected (sub)populations.

An extension activity that we suggest should be employed as part of this artificial selection experiment addresses another of the “big ideas” that drive the revised AP Biology curriculum—the nature of scientific practice and the role of models in guiding scientific research.

In this artificial selection experiment, the model that the WFP parental population is genetically heterogeneous, whereas the self-compatible and inbred FPsc population is not, may be a compelling narrative, but remains a mere assertion and unsupported by evidence. However, students can generate their own data to show that this model is correct, and, in so doing, be introduced to polymorphic molecular genetic markers. Our team of undergraduates at UW-Madison has worked very hard over the past several years to identify sequence length polymorphic genetic markers that robustly distinguish among molecular alleles carried by different varieties of B. rapa and alternative genotypic configurations in segregating populations (Figure 3). Although generated primarily for purposes of mapping mutant loci, the FPsc collection of molecular markers can also be used to evaluate the assertion of differences in extent of genetic diversity and the experiments will reveal the considerable allelic diversity and heterozygousity that exists among individual plants in the WFP population that is altogether absent among individuals in the inbred FPsc population (Figure 2c).

Whether obtained directly through DNA extraction from their plants and subsequent PCR assays or by evaluation of virtual gel images that we will provide as a proxy, students will have observed direct evidence of fundamental difference in the genetic constitution of WFP and FPsc varieties that is the basis for their differential responses to selective pressure.